Waiting for Waiting.*

Waiting.

It’s a fact of life that waiting takes up some part of our everyday lives. We wait for delayed flights to take off, wait for doctors in bland waiting rooms, wait for an exam or test results, wait for the sun to come up or to disappear behind the horizon.

In many ways, we spend much of our lives …. Waiting.

We will always remember 2020 as the year we waited. We waited for news about lockdowns and when they might end. We waited for a miracle vaccine to fight off the dreaded virus. We wait to see when we can once again travel to meet up with loved ones far away. We wait to see whether America will get a new president. We wait to see what the winter or summer will bring.

Its an endless cycle of waiting.

Recently I read an article about an Iranian refugee who took his chances of trying to get to Australia in a leaky boat with hundreds of others. The draconian authorities who intercepted the leaky vessel promptly relocated all aboard to the island of Nauru in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and incarcerated them in a ‘detention’ centre.

That was seven years ago!

The man’s story was heartbreaking. He spends his days like the other hundreds of his fellow detainees waiting to discover their eventual fate.

Seven years!

How heavily time must hang for these poor souls not knowing their fate, relying on the authorities to process their claims with a system that move at glacial speed. It is hard to contemplate what seven years of waiting must do to one’s psyche as they watch as each day morphs slowly into the next with no end in sight.

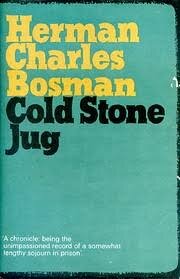

To understand just how heavily the burden of time and waiting envelopes those less fortunate I sometimes turn to Herman Charles Bosman, a prolific literary figure who observed life in South Africa in the fifties. Unfortunately, at the height of his prowess, he had an altercation with his brother in law who Bosman shot in the front garden of his home. To Bosman’s horror, the man died of his wounds, and he was subsequently charged with murder and received the death penalty. The High Court reduced his sentence on appeal to manslaughter, and the punishment handed down was nine years in a high-security prison.

During his time ‘inside’ he penned a wonderful, albeit sobering novel entitled, “Stone Cold Jug.” Within those pages, a particular passage has always stayed with me as he eloquently describes up what seven years of waiting and what the burden of time has on a man

Extract from the story Printshop from Cold Stone Jug

“And talking about time, then doing it and the length of it reminds me of what once happened in the printers’ shop. The head-warder had discovered a whole lot of loose type under the floorboards. How the type go there was in this way: through the years whenever a convict had a job of dissing to do that bored him, he would just take a column of type and drop it through a hole in the floor, thereby saving himself the job of distributing all that stuff, letter by letter, into the various printers trays.

By the time the head-warder discovered that hole in the floor there was quite a mound of type lying there. The convicts all professed great interest and astonishment, averting their disapproval of the kind of person, lower than a rattlesnake’s anus, who could chuck a lot of type under the floorboards to save himself a lot of extra work. That sort of thing never happened in their time, they declared. It must have occurred in the old days when those Australians were in the prison, and the convicts did not have the same sense of responsibility and honour and rectitude that animated them today.

Anyway, the head-warder had the floorboards torn up, and all the type was brought up from underneath, and it was all dumped into a huge box. To a convict named Botha was delegated the task of sorting all that vast chaos of type, letter by letter, into the various partitions in the type-cases. A corner in the printers’ shop was specially fitted out for him. Amid many rows of cases with the box full of assorted type of every variety of size and face before him, Botha would sit on a little stool, patiently picking out and distributing letters that varied from about 36-point Gill Sans Bold to 6-point italic and 10-point Doric.

“How long do you reckon the job will take you?” I asked of Botha, one day.

“About seven years,” he replied.

His answer frightened me a little. I thought of a man outside. What doesn’t happen to a man outside the prison in the course of seven years? The good years and the bad years. The adventures that come his way. The triumphs and the heartbreaks that are bound up with seven years of living. The processions of the seasons, spring succeeding winter and autumn following summer, seven times. A man could meet a girl and fall in love and get married and have quite a number of children in seven years. And he could get a job and get fired and travel all over the world and starve and succeed, and lust and weep and hate and take vengeance—all these things in all these years.

And during this time Botha the convict would be sorting the type out of the box. Only after seven years would his fingers close around the last pica space.

And nothing would be happening to Botha during these years. Just nothing, nothing at all.”

And so, as we wait for 2020 to grind its way to its inevitable conclusion, the one thing that we can cling to is that most precious of all commodity of all, HOPE.

*“Waiting for Godot. Samuel Beckett.”

Bali October 2020

Paul v Walters is the best selling author of several novels and anthologies of short stories. When he is not cocooned in sloth and procrastination in his house in Bali he occasionally rises to scribble for several international travel and vox pop journals.