S-21. A Place Where Phnom Penn Wears Its Heart On Its Sleeve.

Who would have thought that a microscopic virus would have applied a vicelike leash to my wandering spirit? For me, life without travel is fast becoming a dance without music. Its got to the point where I am homesick for places I have yet to visit. To keep my output of articles to an acceptable level, I have returned to my journals, searching for stories that never made it past my often illegible scribbles written on buses, trains, aeroplanes and questionable hotels.

I listened to a BBC podcast recently covering the 25th anniversary of the terrible massacre of eight thousand three hundred and seventy- eight Muslim men and boys in the small Bosnian town of Srebrenica in1995.

Acts of genocide such as this one occur far too regularly and yet, once the horrors of these senseless acts slip from the lead items on television or fall back to the inside pages of the daily newspapers we tend to accept just how man's inhumanity to his fellow man happens on such a regular basis.

In January 2019, (which now feels like ancient times) I travelled throughout Cambodia ending the trip in the nation's capital, the booming city of Phnom Penh.

During my time in that altogether charming city, I knew that I had to make an unwanted pilgrimage to a site where the images and ambience would, I knew, stay with me for the rest of my life.

Where I was headed to is a three-storied building named Tuol Sleng, which, in 1975 was a thriving high school until it was renamed S-21 by the Khmer Rouge and converted into a prison and an elaborate torture chamber.

The streets leading to Tuol Sleng are noisy and crowded with tuc-tuc drivers touting for passengers as they sit cheek by jowl with street-vendors grilling fish over open fires on the crumbling pavements. Across the street are a set of unimposing gates through which, for four terrible years, thousands of Cambodian citizens would pass only to leave as corpses.

Arrival at this place is unemotional and unimpressive as none of the horrors within are apparent as there are no banners, no pointers or flyers, no garish advertising, even the building itself, is uninspiring and rather ugly. But, once one passes through those dreadful gates, there is nothing - absolutely nothing - which can prepare for the kind of emotions one will encounter within.

Absolutely nothing. No amount of pain. No amount of horror. No experience, no thought, no imagining, no sound, no silence.

There is nothing.

Between 1975 and 1979 the Pol Pot regime ruled Cambodia, promising the country peace and prosperity after years of civil war and secret bombing campaigns by the American forces. Cambodians thinking they had been liberated flocked onto the streets to welcome the Khmer Rouge soldiers during the fall of Phnom Penh on April 17, 1975.

However, the promised peace never came, and the residents, almost two million of them were immediately rounded up and sent to the countryside as part of the communist regime's plans to create an agrarian society. Personal possessions were confiscated, money abolished, family ties severed and brutal laws imposed, which saw the population sent to work the land under appalling conditions. Many who were detained in the city ended up here at S-21.

After purchasing a ticket at the entrance to the museum, the visitor is confronted with an original poster that arriving prisoners would have seen written in Khmer, now with French and English translations – announcing the facility's ten "security regulations".

Number six says: "while getting lashes or electrification you must not cry at all." Even under torture, it was forbidden to express one's suffering.

On the opposite wall, there are two striking posters. One shows a scene from April 1975, days after the Khmer Rouge occupied Phnom Penh and forcing its entire population into exodus towards the rice fields, to a life of suffering and death. The other shows a scene from10 January 1979, the day Vietnamese forces entered Tuol Sleng and saved just four children, The beginning and the end of the Khmer Rouge's rule: three years and eight months of horror. The curators of the museum have gone to great lengths to keep the entire complex as it was in those dark days.

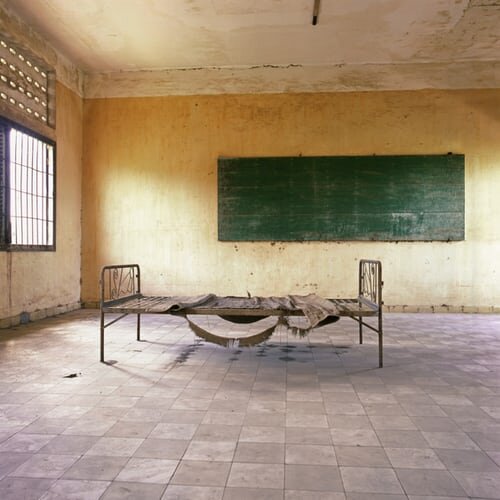

The first room one enters is vast containing just a single metallic bed to which prisoners were chained, while at the far side of the room stands a small interrogator's table and chair. This room was a "VIP cell" for high-ranking prisoners: others were kept either in common rooms chained to the ground or in individual cells just two metres in length and width.

The corridors and rooms are lined with photographs of the prisoners, front on and in profile. Men and women were forced to look directly at the camera lens, some in horror, others in defiance. However, what that they all have in common is that their eyes display not a shred of hope.

Many are mere children; most are young people. There are images of mothers holding their babies, all condemned to die. Of the 18,000 who had been inmates of Tuol Sleng, just seven survived.

As you walk these corridors, not as a prisoner - (for you will walk out again) you begin to understand, with the luxury of freedom as your guiding light, how far we can go when we want to, into that valley of hate when no-one is at hand to stop us.

I pause at one particular picture of a man, perhaps in his thirties who stares emotionlessly from the frame in which his image is housed.

I wonder about him.

Everything he might have been. The children he never had, his family, his endeavours, his loves, his likes, his hopes, his dreams and his fears are all there. All of these sentiments seem to crowd into this one picture. His sad, resigned eyes stare across the years directly at me.

Being within these walls is a sobering experience as you limp from room to room feeling your settled world begin to unravel. Your brain tries in vain to filter and to file what you are seeing, sharing this terrible space with the thousands of ghosts of S-21.

This place has become one of the silent places in my world, where there is nothing that can be said. No words, no philosophy, no religion, no god, no song, no music of any sort or kind. There is little solace or balm to ease the images that cannot be unseen. That silence, coupled with the stares of thousands of eyes from the photographs that stared back at me, will live with me forever.

There is nothing to be said.

Nothing at all.

Bali, July 2020